As a therapist, I am always curious about shame. It has a particular felt experience, for example, after presenting something, I know I’m experiencing shame if I’m left with contracted feelings about myself, sensations of tightness in my chest or a desire to be invisible.

Whilst reading Allan Schore’s work on ‘Affect Regulation’. I discovered the work of Helen Block Lewis and her concept of shame as an ‘affect emotion’

The basic assumption of this article is that shame, is a painful and visceral ‘attachment emotion’[1]. Shame can create mortified separation, which organises the self to hide or defend against contact. For this reason, shame might be described as an ‘anti-relational’ affect and shame-based people may sometimes be labelled as difficult or resistant. When unattended, the subtlety of this dynamic can recreate a shaming, frozen environment for both client and therapist.

Lewis, a psychotherapist, researcher and writer practicing from 1940s to 1980s, is noted, as being one of the most prolific researchers on shame was one of the first to annotate its phenomenology. She called it the ‘sleeper’ emotion in therapy because its nature is silent.

During her research, which consisted of reading hundreds of transcripts from a variety of therapist’s sessions, Lewis noticed shame shadows in the undercurrents of the therapy, which were not attended to by the therapist. She labelled this ‘bypassed shame’

Phenomenology of Shame

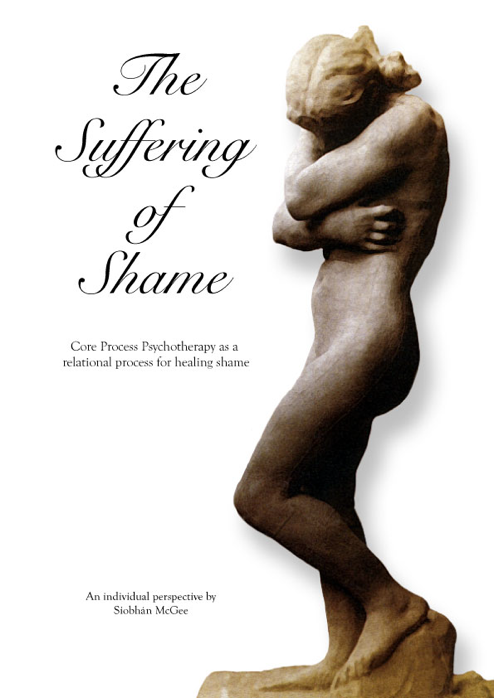

Rodin’s sculpture ‘Eve’ (pictured) embodies the phenomenology of shame. The word originates from ‘Kam’ meaning to cover or hide. In the image of the sculpture Eve hides her face, averting from the gaze of another. Her heart is covered to protect the being at her soft and vulnerable core and her body is contorted away from relationship. Shame does not allow us to let anyone else into the painful inner experience and it further isolates us by an internal message that ‘it is weakness to show vulnerability’. Shame likes secrets.

This speaks of the absolute self-conscious experience of a separate and disconnected self. It is an internalised experience of ‘badness’. This is different from the experience of guilt, which says ‘I have done something bad’ and is an experience of feeling on behalf of another. Shame is the embodiment of the statement ‘I am bad’.

Lewis was also one of the first to talk about shame in physiological terms. Most definitions of the word shame involve the world ‘painful’, this again hints at the physical experience, which induces hyper-arousal in the nervous system. This also indicates the close links to trauma where people often feel and internalise a sense of badness or uselessness. Traumatised people often carry shame which does not belong to them.

A phenomenological approach is resonant with the relational mindfulness inherent in Core Process Psychotherapy because it invites awareness of the essence of being from moment to moment. This mindfulness to what arises in the present moment means that Core Process does not overly focus on telling stories ‘about the past’. The past emerges in relationship to what is happening in the present moment and therefore it is vital to pay attention to the relational space and what is emergent. A Core Process therapist does this through phenomenological dual attention to the client’s process and the therapist’s own embodied resonances.

The Dynamics of Shame

Shame is a recycling emotion where we experience shame for feeling ashamed which inevitably leads to denial. Lewis suggested that shame’s contagion hovers silently in the space as both therapist and client collectively bypass it like the proverbial elephant in the room.

Some of the dynamics I have noticed in my work with clients’ shame is often around the client’s gaze being met at the point where contact may feel excruciating. It may indicate a fight or flight response and once again suggest shame’s link to potential early relational or attachment trauma.

Hostility

There is often a sense of hostility around shame, which can be expressed as a feeling tone of anger or manifest in withdrawing and it is for this reason that I believe shame-based clients may be labelled as ‘difficult’.

Secrets

The internal world of shame often encompasses and protects secrets and the terror of being found out. This causes isolating behaviour as we try to stay safe from the world’s watchful and shaming eyes.

Subterranean experience

When deepening into this territory several clients have connected with an archetypal energy of a hunched up creature living in damp cold conditions reminiscent of Golum in ‘Lord of the Rings’. Shame constellates around the needs of this ‘creature’ and is often accompanied by a feeling of disgust and rejection. Sometimes when clients experience relationship with this part there can be an opening to feelings of deep compassion.

As a practitioner of mindfulness relational psychotherapy it has become very important for me to listen out for these textures and tones to see if the shadow of shame swirls silently in the space.

Core Process as Relational Mindfulness

Shame, rooted in ‘relational’ wounding, is felt as a response to the real or imagined negative gaze of another and sets in the body as a rigidified sense of ‘badness’ further separating us from contact. My assumption is that healing shame is best worked on through relationship to ourselves and others. In working with shame, I recognise that everyone experiences it, our particular tones may be different, however it is a universal emotion, which is one of suffering. By connecting to this, not owning it as my shame, but simply as shame, the possibility for healing and connection is greater. Many recovering addicts talk of keeping the addiction secret and the healing that arises coming out of the isolation of shame into a community where people directly talk about it.

Core Process as a mindfulness-based relational psychotherapy, has its roots in Buddhist psychology which is a holistic spiritual philosophy of the interdependence of all things. From a Buddhist perspective suffering is created through a sense of being separate, which contributes to our isolation and disconnection. Shame is akin to the experience of what the Buddha called ‘dukkha’ or universal suffering. In that experience, we are disconnected, separate and like Eve, cast out from the Garden or one’s sense of feeling connected.

In Core Process Psychotherapy, the practitioner’s awareness practice is a vital part of the work. When I practice present moment awareness with clients, a wider relational field is available to rest into and be held by. This creates the possibility of spaciousness and also opens a more heartful connection. The Heart Chakra energetically is seen as the bridge to relationship, so in my work, when I am able to come from an expanded heart, warmth is tangible in the space. My personal experience is that the qualities of genuine warmth, friendliness and equanimity create a non-shaming environment where it is much easier to be curious in a non-defended way, for example, I may wonder whether there is shame in the space and inquire what the client is experiencing in relationship to me.

Lewis felt it was vital not to loose shame in the field. I have noticed that the more I open to the possibility of its existence in the therapy room, the more spaciousness there is to what arises. This has often included working with the gaze and whether I look at the client or not. Sometimes it is safer for a client, to have me avert my gaze and instead use my voice as a way of making contact. Some people have found it easier to look at me if I am not looking at them and for some clients this has been a fundamental aspect in the therapeutic relationship. It has been important to enable the client to create the safety they need in relationship rather than wondering or exploring what the safety is about which could create more shame around their need for safety.

Example

To protect confidentiality this is a generalised example based on clinical work.

Clients may come for therapy because of extreme anger, causing considerable distress in close family or work relationships. Exploring the theme of shame enables a person to connect at a deeper level with it. Underneath the anger may be a sense of inadequacy. By exploring this territory in our moment to moment relationship, clients can contact core material around the internal belief ‘I’m not good enough’.

These beliefs are often related to past experiences and the feelings that have lurked unknown in the body for many years.

I often explore the inner shame voice and invite a client to give it a shape and form, tone of voice etc. Often the shame voice has had some protective purpose and developed to keep the person safe. During my work, I have found that mindful breathing often helps clients to develop kindness and soften towards self-acceptance. Clients often prefer to have a visual cue e.g. visualise a colour or dark smoke while breathing out the anger/shame and breathe in clear light into the chest area and I have also used aroma as a part of this process.

Clients have reported that this is a way of helping diffuse the rage and shame and Dr Paul Gilbert has written extensively about the use of compassionate images to help soothe the threat system. When client’s begin to actively practise awareness, they open into a less shaming relationship with themselves and may have different responses to situations that had previously been triggers for the rage. One client noticed that connecting more deeply with this inner ‘self’ was positively impacting relationships with others.

As therapists, we need to do our own shame work to ensure it doesn’t become the hot potato in the therapy space. Paying mindful attention to shame creates space to welcome its particular energy into the relational field. Deepening mindfulness and attention to body awareness has helped some clients, particularly those with a history of traumatisation, to connect with self-compassion and contact a relationship of deeper self-acceptance. This often indicates a clearer connection with their witness consciousness, where a person is becoming engaged in a process of noticing their own process rather than becoming it.

References

Affect Regulation and the Origin of the Self, Allan N Schore, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates (1994)

Shame and Guilt in Neurosis, Helen Block Lewis, International University Press (1971)

Shame Interpersonal Behaviour, Psychopathology and Culture, Paul Gilbert & Bernice Andrews, Oxford University Press (1998)

The Voice of Shame, Silence and connection in Psychotherapy, Robert G Lee & Gordon Wheeler, Gestalt Press (2003)

Mindfulness & Psychotherapy, Edited by: Christopher K Germer, Ronald D. Siegel, Paul R. Fulton The Guildford Press (2005)

The Compassionate Mind, Paul Gilbert, Constable (2009)

Picture: ‘Eve’ by Rodin, Royal Academy Exhibition Postcard (2006)

[1] Lewis, H.B. “Narcissistic Personality’ or ‘Shame-prone superego mode:. Comparative Psychotherapy, (I,59-80) from Schore, Allan.N. Affect Regulation and the Origin of the Self, the Neurobiology of Emotional Development (1994, p201)

© Siobhan McGee, October 2006